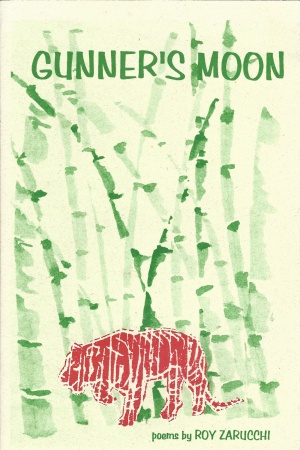

Gunner's Moon

Gunner's Moon is a collection of poems written by Cpt. Roy Zarucchi of the 609th Special Operations Squadron during their time as part of Operation Steel Tiger. I managed to acquire this copy from an estate sale on eBay. To whomever was bidding against me, I hope that this is an adequate consolation. I wanted to preserve and share these stories with everyone. IHF presents these stories in their unaltered original text as a historical document.

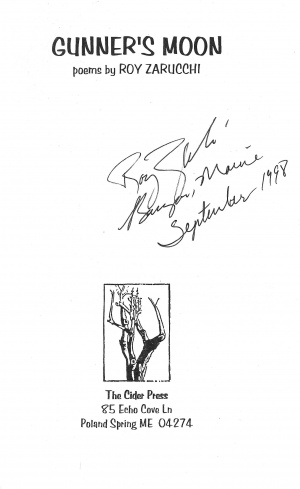

The copy of this work in the IHF Library is signed by Zarucchi. "Roy Zarucchi. Bangor, Maine. September, 1998".

Normally we would not post the entirety of a book on our site, however, Roy Zarucchi retired as a Major and has unfortunately passed away in 2011. The Publisher information listed in the book does not seem to be valid any longer. Either the publisher has become defunct, or else the sole proprietor of the publisher has also perished since the book was published in 1998. We have made all good-faith efforts to contact anyone connected with this publisher, but have not been able to do so. As such, we have decided to post the entirety of the work here to preserve Roy Zarucchi's legacy since the book is out of the print and only limited quantities were produced. We are doing this on a good-faith basis and not attempting to infringe upon any copyrights. If you are an agent or representative of the publisher and wish this content to be removed, please send us an email and the information will be removed immediately.

Preface by Carolyn Page

TRUCKS RUNNING THROUGH LAOS

Some nights in rural countrysides the only sounds are owls bathed in moonlight. Farmers dream of breeding bulls, dragging stones, setting fence posts. In our house my lover plows in foreign soil, and I lie down with the enemy. From nowhere they come through thin skin of dreams, they slip between the sheets, aim and take prisoners, and I am captive too, for I am war-blind to my lover's lens. I see no tracers flash nor hear strange tongues. No splash of napalm, no slow death's fiery orange glow in sweaty tropical nights. "Smitty, watch out!" means nothing in the dawn. "I'll kill the lousy son of a bitch!" rings out and I cannot touch this rage until it cools, "Roll in! Break right! Pull out!" The red-lit cockpit charts mark targets to be blown—convoys of trucks crawling along the jungle floor. It's a private Hell, an undeclared war still raging in an undemilitarized zone.

Part I—Toy Soldier

The Wall

Give 'em a place to bang their heads.

Build it long and low out of sight from the White House;

sweep up the medals and litter at sundown.

War Zone

In the hills to the east of San Francisco Bay, the vacant lot next door turns green for two months every year—signal for the battles to begin. Dig the foxholes and don the army surplus belt, it's dirt-bomb hand grenade time and spit-through-the-front-teeth gun fire flying with the voice of tail-gunner Joe McCarthy rat-a-tat-tat those goddamn, godless, commie-pinko bastards, while we sing Onward Christian Soldiers join the Boy Scouts then duck and cover having been born on the eve of Seig Heil but, at that point, having lived only so far as Are you now or have you ever been...?

Rockfishing

—for a stepfather who liked to teach lessons

With ball of chalkline, can of guts, and gunnysack we started down the bluff.

"Put your foot where I tell you," you said. You went ahead.

My small hands gripped random rocks and roots. I wished for your touch, your arms, your face.

Later, on the splashing rocks, I whined, "What're we fishing for?"

Then suddenly, out of the blue-green sea, from beyond my mind, on the end of my line, it came. The Cabezone grinned, grim in the watery light. Maroon or grey or green, it thrashed. You pried loose the hook and threw him in the sack. We started back. "Follow me," you said, and, with a wag of burlap bag, you went ahead. Scaling up a hundred feet or more, like a Bighorn sheep, you climbed. I looked down at the surging sea below, beneath the seagulls' backs. "I Can't!" My words flapped in between the sea lions' barks and up the face of the tilted, tumbling bluff. "I can't!" "Son, there's no such word!" you shouted back.

Volunteering

Three boys are at the quarry pond scooping tadpoles into Mason jars when up comes Billy Kurtz. He sneers, stands atop the biggest rock and strips, crouches toward the boys across the pond, pale skin taut, fearsome tool swinging, he springs into the pool then surfaces before them. "SISSIES!" he jeers with a smirk. Towers above, dripping on their faces. They fumble, strip, and wade in, hairless and pink, no match for Billy, they laugh and yelp as he seizes each in hairy arms and roughs them up. Later, as they dress, he lights a cigarette, eyes their rosy buttons shriveled from the cold, blows the smoke their way. You're my boys now. Tell anyone who wants to mess with you that you belong to Billy Kurtz.

Seminary

Habits dwell in cells, like silence not to be broken, no words uttered from evening prayers till morning after breakfast; clothes, not a matter of adornment, but protection against eyes of the world. Matins, Prime, Terce, Sext, None, Vespers, Compline: the seven hours bind us into order, string us up in the thrall of rote—the Rosary—lips begging "...the fruit of thy womb... now and in the hour of our death..." the mind disrobes a dark woman while the oscillating mouth dissolves to a smile around each prayer. Fingers linger on the nubs of beads, and the confessional door at the rear of the chapel clicks open clicks shut.

Port Call

Thanksgiving Day comes early this year, eight November sixty-seven. Relatives gather in a seedy Central Valley town to say goodbye to husband-father-nephew-son. The flight departs at seven, so dinner's served at two. At the table in dress blues, guest of honor studies the turkey that in its short life never made a flight. The father is detached and proud, the mother sullen. A crippled aunt watches television while another dances with two whiny kids. The wife emerges from the kitchen, hugs. Passport, shot records, orders tucked in canvas bags. No taste left for food or kisses, just good-bye. Lifting off from Travis, the airliner fills with cigarette smoke and forced smiles of hostesses who'd rather be working the luxury routes. First stop, Honolulu. The airport has a pool with water lilies; blooms explode over genteel orange carp who eat at will, wave in fiery nonchalance, grow smaller, as the silver bird roars West.

Survival School

King cobra is the ruler of this reptilarium, and it's feeding time. He looms, thick black cable, spreads his hood against a hissing, four-foot monitor lizard. They parry, skirt, then in one quick move King gulps the head. The lizard sees the night, bites darkness, gives a final wave of tail as sinews coax him down. The spectator students swagger off to lunch, then board the bus. It's three days in the jungle with the Negritos, loin-clothed Philippine pygmies. They start a campfire with two sticks, steam unknown foods in bamboo tubes. Wet green night swallows flyboys whole in their government issue tents. In the morning a distant earthquake rumbles. The Negritos trap a monkey which vanishes into a sack. Other natives appear from jungle edge, six of them holding a giant bat. They hoist it in a crucifix of fur and leather, ten feet from tip to tip. Their teeth glint white as they point to the arrow through its heart. "You eat! You eat!"

"Naked Fanny"

Nakhon Phanom. Why bother to ask what it translates to? It's plain: the lines of planes on metal mesh in black and camouflage—no stars, no stripes. Skyraiders, Gooneybirds, Invaders: propellers at attention await the setting of a red-dust sun. Red dust everywhere shoals up to crown the roads mosses the dark brown clapboards of buildings, crochets our collars and cuffs. There used to be a jungle here, with towering teak a hundred feet or more home to tiger, peacock, pheasant, now cleared and groomed by truckloads of Thais with rags around their heads, who have forgotten that "Thai" means "Free" or that their flag once bore a white elephant.

Part II—Stripes For a Steel Tiger

Dollar Ride

The orientation flight, a little package wrapped up in night. "Light haze and smoke with five mile viz," the weather wizard says, then last night's gunfire, AAA reports from Intelligence.

Out on the ramp the crew chief smiles, salutes. The bomb bay's pregnant with destruction—six frag clusters and three Funny Bombs, leftovers from plans for Japan. Under the wings, napalm hangs in sleek silver penises. Switches click; propellers churn.

"Nimrod 32 cleared for take off." The wet air swirls across the wing and lifts the Douglas Invader into night as it lumbers "across the fence" into the yawn and maw of Laos: destination Steel Tiger a fifteen minute ride. Running lights are dowsed.

Contact with a spotter plane: "Nimrod this is Nail 12. I've got a convoy headed south. Twenty of 'em with their headlights on. I'm putting down a mark." "Roger. Got it." The props go out of synch and the Nimrod turns and drops. Five-thousand. Master switch is hot. Four-thousand Gimme a nape off #2 Three-thousand 37 mike-mike comin' up right. Two-thousand You're hot. Fifteen hundred Pickle. BREAK LEFT! BREAK LEFT! Tiny red golf balls float past on their way to a final popcorn puff of flak in the hazy dark above. Nine more passes—fifteen trucks get through.

De-briefing: "How many rounds fired at you?" "About four-thousand." "How many trucks destroyed?" "Killed five." "Thank you, gentlemen." "C'mon new guy, let's get to the club. We're buyin'.

The O'Club—an air-conditioned broth of stale scotch and curried entrees where most of the social life swirls. Nimrods take over the bar at midnight and slosh around till four or five. Others drink at their own peril as an occasional body flies over the bar at the smiling Thai bartender. "Keemau! Keemau! You drunk, sah, veddy drunk. You maybe hab one more? Yes?" "Hell yes! Why not?" The juke box blares with records that are never changed. Someone might complain if his favorite song vanished: the only way to close his eyes and touch his lover's flesh 12,000 miles away. Flight suits spot with sweat and beer and smell of the sour Mekong where they're washed.

Cheney's going home tomorrow. He strips to his skivvies, jumps up on a table, and pops a champagne magnum between his legs, ejaculates in bubbly on the soppy cheering crowd. "Let's have a hymn," shouts one. "Let's have a hymn," another. "Let's have a hymn!" "Let's have a hymn!" "Yeah!" "Yeah!"

HIM, HIM, FUCK HIM!

The melee fades as some drift into the dining room for a dinner of bacon and eggs. Outside, day breaks, as the juke box plays for the twelfth consecutive time: If you are going to San Francisco, be sure to wear some flowers in your hair. If you are going to San Francisco, you're sure to meet some gentle people there...

In The Marketplace

You bend, teak sapling saronged in finest mauve and purple silk, then rise, gold chain glittering in the hollow of your breasts. Hand filled with cats-eyes, you hold each gem against the sun to catch and bend the light, to pierce the eye with ah such cunning brightness as if sapphire stones could blind a man to ginger-scented hair or the silk wrapped dark Laotian night.

Chapel Service

This is the day for Airman Gray. He enters the chapel before Mass and sits in the last pew. Alone he ponders the "whys," fingers the muzzle of the M-16 across his thighs. Security's such a boring job. No one ever attacks. Mind wanders off to the little brown girl in Bangkok who gave him a dose; to his Momma, who wouldn't approve. Gray scans the Stations of the Cross along the walls, and in a helix of fever rises from the pew, takes aim, and fires: picks off the Stations like so many skeet then turns to face the altar. Blows the loin-cloth off the Jesus crucified in memory of Chaplain Jones who yanked the G-string off the stripper at the USO show, then took communion on the spot. Plunks the bird from the hand of St. Francis then wastes the Virgin Mary through the heart. The chapel fills with kordite fog as plaster bodies bounce and break and brass shells clatter across the floor, barely heard above the sobs beneath the gaze of half a Jesus.

=Gunner's Moon

Maybe Jimmy Beauregard knew, as he strapped himself into the right hand seat that night, what none of the rest of us believed for a while. And as he flew across the fence, did he think for even a moment upon the conversation he'd had the night before? How he'd stubbornly maintained, in expanding Southern drawl, that you'd see the bullet that would get you well before it hit. "Either it's got your name on it or it don't," and slapped the red-checked tabletop, calling for another round.

And is it not with infinite skill and grace that his pilot plummets them out of the hazy, purple night, brings the A-26 to that eyes-wide depth beneath the smoking flares and runs the roads splashing napalm firing the '50's into truck cabs Jimmy throwing the switches urging him on jeering the dead?

Pulling up and away for the seventh time, he spies the lines of tracers gliding toward the nose, then focusses on one sees it glowing in bright orange fever, burning through the windscreen, exploding his right side as it hurries on its way. Is there any motion to be seen in the half-light of a rising gunner's moon as Jimmy's spirit drifts out of that meandering river valley and floats above the jutting ridge of karst?

—for George B. Hertlein

Repercussions

Above the crimson-lit instrument panel, just to the left, a red-guarded switch says: "Emergency Bombload Jettison." Raise the metal cover, then flick the toggle up—like turning on a light.

I had to do it once—one engine gone—a whoosh, tropical air rushing up through opening bomb bay doors, then all came tumbling out: the frags, the funny bombs, the napes—a great flash and shockwave from the jungle floor swept us up in sudden lightness toward a dark heaven that would have to wait for at least another day.

Meeting In Hawaii

Halfway through the one-year tour—R & R. We meet at a semi-posh hotel along the beach, where the twin beds get shoved together for five days. How strange to see again your red hair and naked whiteness against the cool flowered sheets, your scent heavy with orchid and hibiscus,

my mind at altitude, 8,000 miles to the west. How odd to sit in the shaded patio at Fort DeRussy, sipping Mai-Tais, discussing our children and friends back home, whose faces I cannot conjure—how odd to see you off, then immediately forget, as if each day had been a lotus leaf;

Then, on the return trip through Bangkok, I find a deep bronze woman with small breasts that I take with my mouth; scents of ginger, garlic and teakwood fires surround her, as she, with a smile without a hint of love, reminds me of who I have become.

Dreamscape

On the patio at five in the morning, night-flyers slouch in sour flight suits, amid the buzz of giant rice-bug locusts. They're doing loops and rolls, crashing into screens—Br-r-r-x-x, br-r-x-x, clackety-clack. Too much, so Tom starts spraying them with paint, first red, then white, then blue, a gaudy patriot's display: tiny plastic 'copters spinning to the ground. Willie's reading his mail: "What's this mean, this letter I sent to my wife? 'DECEASED, RETURN TO SENDER?' It's supposed to be the other way around." He bites the cork off a quart of Chivas, spits it into the waste can, sucks on the bottle, passes it on, then dozes, the letter in his lap. Conversation fades as men fall asleep in plastic chairs, take flight into dreams in the steamy sky of morning.

The Minimax

In his windowless, air-conditioned office, Floyd B. Nutter sifts the papers of the war, fills in the blanks and squares, doing his part in Saigon. A cup of coffee in the morning, then check the message traffic from Clark Air Base and Washington. It's he who passes on the words, turns them into deeds.

"General, sign these letters, please." "There. It's done. Good work, Floyd. Oh, before you go, I need you to work up something. We have to speak to our combat crews in a general but meaningful way. McNamara says our losses are too high. We can't be winning and have high numbers. Can we, Floyd?" "No, sir, I don't think so." "Good. So here's what I want to say." He hands the major a sheet of memo pad: "MINIMIZE LOSSES. MAXIMIZE EFFECTIVENESS." "Oh, yes, that should do it, sir—strong, direct. I certainly couldn't improve on this. I'll send it right away." "And have our people post it everywhere the flight crews go. They need to see it." Nutter drafts the message, zings it off, then pours another cup of coffee, walks over to the far wall, and stares at it as if there were a window.

Monty's Ice Cream Parlor

Monty's was the place to go on nights off, a narrow teakwood frame stilted over the Mekong, where we'd sit on sticky chairs, sip Sing-Hai beer. I can remember the photograph I took at twilight from the window that looked out toward Laos. In the foreground, a darkening barge floats past, as the lights and fires of Thaket flicker on the far shore. To the east, behind the town, jagged escarpments of karst, etched intaglio of a sinking sun, steep walls of limestone thrust against Invaders, who, at the moment of the shutter's click, are captured winging eastward. They are only specks to the unpracticed eye. If I had that photo now, I'd tell you they were there, point to them with a pencil tip, "Look! Look!" And you would squint and shake your head in kindest disbelief, then smile politely as I told you Monty never served ice cream.

When The Tiger Lick's Its Paws

In the dream the steel tiger springs, and I escape into the red of his eye, soar above karst brainscape. Riding in the right seat I am banked, jinked, rolled in, pulled out; throwing switches, adjusting propellers, opening bomb bay doors. You, my faceless pilot, in the red-lit dark of the cockpit, leave me half-alone. You breathe into the hot mike, and curse when tracers stitch us. Bombs spent, we count the burning trucks, head west and climb to angels six.

Each night the Dark Angel lurks in the light of flares, the white of moon, the swatch of silk in the blood chit.

The trucks are rolling, rolling south, skirting the pock marks of Ban-La-Boy Ford down meanders of rivers they slip between the breasts of karst they twist to the mound of the cliffs at Tchepone.

II

Night after night the gunners of Tchepone fire their volleys into the darkness where red dragon tracers whip the wings. The gunners of Tchepone are weary from bombings, their feet are coming through their boots and they nearly always miss. By sunrise they grow weary and lie down in tin and cardboard huts where Lao girls with delicate bones pour wine, steam rice, steep tea, sleep in the jungle green shade.

III

The welcome home team is wearing green, and the table is hard and cold. We can't get it all. One shall be taken. One shall be left. Forceps. Then you can go home. Sponge. You're taking this well. You'll be home with the family in no time. Suction. Let's hope it doesn't fester. Suture.

IV

Do I remember: the glow of fear beneath the flares or on moonlit nights drive the car over the rumble of the road, hear the props grind out-of-synch feel the urge to turn left speed up as in a dive toward the lights of a distant farm

Remember: the five who flew away we packed their possessions minus Playboys and rubbers wrote the letters of war: Dear Mary... Dear Susan... how they might have been us and were in the seep of waking remember: the tiger licking its paws how hunger returns

Hide

The six-foot rattler's hide lies wrinkled, annual stripping of another life. The horny rings adorn a jacquard print like clothes of Bankok ladies of the night or Auschwitz lampshades, delicate and light. When his flesh itches or rubs him wrong he wriggles out, tries to abandon what he is, reminded always by vestigial legs, that once he was a lizard in a field of stones, knew which land he must defend, which sun-bleached skull to hide behind, or having struck his prey he might take cunning flight across the tops of jagged rocks.

The Nimrod

In the Maine woods, he shuffles about a rustic cabin, stroking his beard, reading letters written, never sent. On north wall, dust gathers on rifle next to a snatch of pelts. He pats the woodpile beside the stove, grabs a piece, stuffs it in. Smoke puffs to rafters where bats live. Scrolls of papers stand in corners, blueprints for inventions never dreamt. In the center of a table, covered in old silk, a terrarium with serpentine vines that push against glass walls. He speaks to jars of pickled polliwogs on shelves, to his collection of limestone rocks and rough sapphires. He knows their names. Under the window, a teakwood coffin, filled with earth, "Nimrod" hand-lettered on its side. Here, sweetgrass and wild oats for locusts in tiny bamboo homes. He doesn't flinch as a bat swoops down, lands on his arm, needle teeth glinting in the half-light. He plucks a locust by the wings, an offering: "You eat. You eat."

Glossary

AAA - Anti-aircraft artillery; most common type encountered in Steel Tiger was 37-mm which created flak bursts, and ZPU, which was usually fired from gunmount sets of four, providing a highly concentrated screen of fire against low altitude aircraft.

A-26 - A fixed-wing medium-weight dive bomber driven by two Pratt & Whitney reciprocating engines. First designed in the '40's, the Douglas A-26 was used extensively in Korea for night interdiction, then brought out of mothballs for missions in Southeast Asia and other miscellaneous skirmishes. By the end of the '60's all but a handful had been shot down or lost on the karst, and most of the remaining aircraft were retired.

BDA - Bomb Damage Assesment: best estimate of damage inflicted as could be made from the air.

Ban-La-Boy - A "deserted" village and high traffic fording spot for NVA trucks at the north end of Steel Tiger, just southwest of the Mu-Gia Pass.

Blood Chit - A square of silk carried in the personal survival kit, which promised payment in gold for the safe delivery of any downed American airman.

Delta 7/22 - "Delta " was used to designate rendezvous points for organizing airstrikes along the Ho Chi Minh Trail, an extensive network of highways through Central Laos.

'50's - The eight 50 caliber machine guns mounted in the nose of the A-26; highly effective against truck convoys but risky because the flash and flames from the muzzles swept over the nose creating an excellent target for AAA gunners and lowering visibility inside the cockpit with a gunpowder fog.

Funny Bombs - 500 lb. cannisters of incendiary clusters. These were highly effective against rolling stock. They would airburst at about 1,000 ft. covering an area about the size of two football fields with thermite/thermate.

Invader - The factory name for the A-26A.

karst - Limestone mountains, much like a steep moonscape. This type of terrain is common in south Asia in areas formerly sea bottom, being composed primarily of fossil shells.

Nail - Call sign for an 0-2 forward air controller spotter plane.

Nakhon Phanom (NKP) - A base located in NE Thailand about ten miles from the Laotian border, closer to Hanoi than to Bangkok. It was the main base for propeller driven Air Commando aircraft.

Nimrod - Call sign for the A-26A night sorties from NKP. Also the designation of any crewmember of the A-26A assigned to the 609th Air Commando Squadron.

Steel Tiger - Department of Defense code name for the bomb zone in central Laos.

Tchepone - A village and valley area towards the south end of Steel Tiger.

Thaket - The "sister" village to Nakhon Phanom village, Thak being on the Laotian side of the Mekong River, the latter on the Thailand side.

Author's Biography

Born in Northern California, Roy Zarucchi attended parochial school, then the minor seminary at Mountain View with the notion of becoming a priest. At age twenty, he abandoned these plans and finished college at St. Mary's, Moraga, after which he opted to teach Latin in Quincy, CA. His plans were altered by the Vietnam War where he served with the Air Commandos as bombardier, flying 163 night dive-bombing missions in the A-26 over the Ho Chi Minh Trail in central Laos. He later wrote personnel policy for the Air Force at The Pentagon, then re-tired and moved on to college teaching. He ultimately got out from behind desks, becoming in his forties a professional potter and sculptor. An emerging poet at age fifty-six, he has now published two collections, the first being Sparse Rain (Pygmy Forest Press, 1991) and is widely pub-lished in the U.S. and Canada. From his farm-home in the hills of Downeast Maine, he co-edits the literary arts journal Potato Eyes with his wife Carolyn Page, also a published poet. When not planting poems or throwing clay, he tends a woodlot, farms organically, and researches 19th century American history.